Roots in Antiquity: Wrestling Traditions of Early China

The Mythic Origins and Royal Patronage

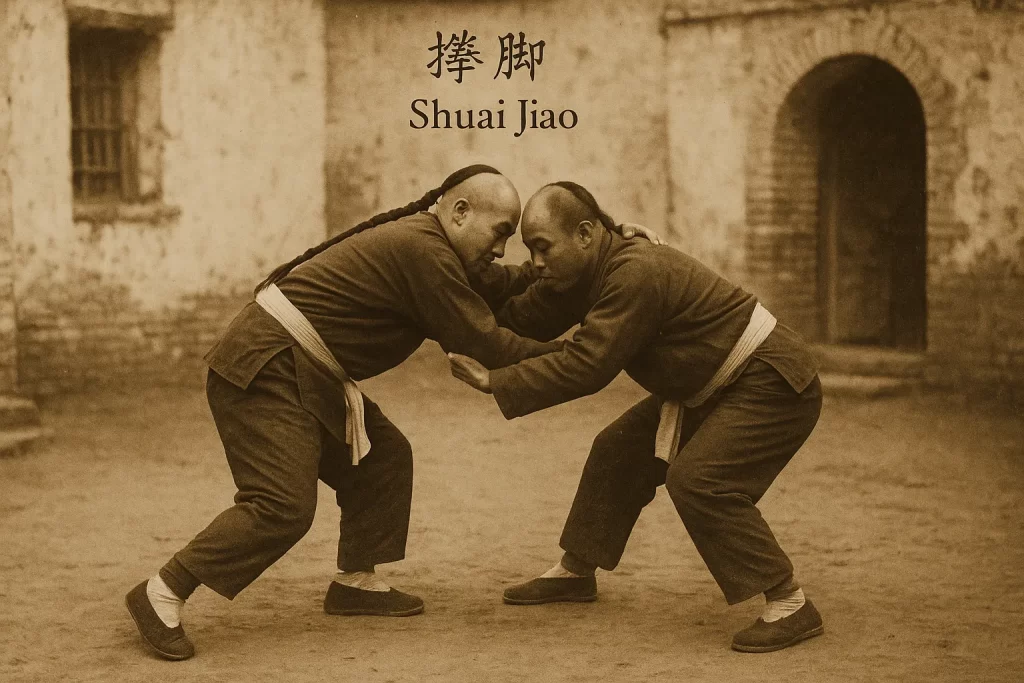

Shuai Jiao, often referred to as China’s oldest martial art, traces its lineage to the dawn of Chinese civilization. In mythic accounts, wrestling appears as early as the time of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi), whose legendary general Chi You is said to have engaged in fierce grappling contests. These early depictions weren’t mere stories—they reflect a broader ritual and martial role of wrestling in prehistoric Chinese society.

During the Xia and Shang dynasties (ca. 2070–1046 BCE), early forms of Shuai Jiao were already practiced among warriors as well as within court circles. Wrestlers were often presented at royal courts as entertainers and were trained for combat simulations. Wrestling contests were integrated into rituals, military training, and sometimes as a symbolic form of justice or dispute resolution.

A particularly important early form was Jiao Li, an ancestral wrestling system that predates the formal term Shuai Jiao. Jiao Li was codified during the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) and became an essential element in military exams for warriors.

Note: Jiao Li is not identical to Shuai Jiao but is historically and philosophically its precursor. Over time, Jiao Li’s combative aspects evolved into the formalized Shuai Jiao system.

Military Utility and Institutionalization

From the Western Zhou to the Warring States period (770–221 BCE), Chinese states increasingly institutionalized wrestling as a method of military conditioning. Soldiers were required to train in grappling not only for battlefield applications—where close combat was frequent—but also for strengthening discipline, stamina, and group cohesion.

- Wrestlers were recruited into elite palace guards and shock troops.

- Commanders often held tournaments to assess the physical prowess of conscripts.

- Techniques emphasized balance disruption, leg sweeps, and control—vital for armor-clad confrontation.

The Art of War by Sun Tzu, although not mentioning Shuai Jiao directly, reflects the emphasis on close-range strategy and body control that characterized martial practices of the era. Shuai Jiao emerged as a reflection of these principles in embodied form.

Ritual and Cultural Functions

Wrestling was never confined solely to warfare. In early Chinese society, it served a broader ritualistic and community-building role. Seasonal festivals, particularly during planting and harvest cycles, often featured wrestling matches in villages and towns.

These contests held multiple meanings:

- As acts of physical tribute to deities and ancestors

- As demonstrations of masculinity, vigor, and social standing

- As a means to resolve disputes without bloodshed

In northern regions like the Central Plains and the proto-Manchurian territories, where nomadic influences mingled with Han traditions, wrestling became a shared language across tribal and ethnic divides.

Consolidation in Imperial China: Han to Tang Dynasties

Han Dynasty Formalization and Bureaucratic Recognition

The Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) marked the first major institutional recognition of wrestling within the imperial apparatus. Emperor Wu of Han, in particular, valued martial skill and promoted military arts as part of civil service examinations for border defense units.

Jiao Li became a structured part of military academies:

- The Jiaodi Yuan (Wrestling Courtyard) was established as a training center for elite troops.

- Wrestlers were categorized into ranks and trained alongside archers and cavalry units.

- Manuals and oral transmission methods began to codify technique names and progression systems.

This bureaucratic formalization laid the groundwork for the later terminology of Shuai Jiao. The emphasis was on practicality, battlefield application, and body conditioning.

Cross-Cultural Exchanges and Steppe Influence

The Han dynasty’s expansion into Central Asia and frequent contact with nomadic tribes, especially the Xiongnu, brought Chinese grappling traditions into dialogue with foreign systems. Nomadic wrestling styles emphasized raw strength, throws from horseback, and non-formalized training—traits that would later influence northern Chinese variants of Shuai Jiao.

The Silk Road fostered further cultural interchange:

- Turkic and Persian wrestling techniques merged subtly with native systems.

- Techniques such as belt holds, hip throws, and backward trips became more prominent.

- Wrestlers from different backgrounds often competed in court events, offering a hybridization of styles.

This hybridization would become especially notable in the Mongol-influenced branches of Shuai Jiao centuries later.

Tang Dynasty Revival and Folk Tradition

The Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) was a golden age for Chinese culture, and physical arts—including wrestling—flourished under its cosmopolitan atmosphere. Court records mention wrestling performances as part of diplomatic events, especially with envoys from Korea, Japan, and Central Asia.

Meanwhile, folk traditions of Shuai Jiao persisted and expanded:

- Village-based wrestling schools developed localized techniques.

- Sects emerged that passed knowledge through family lines or monastic circles.

- Shuai Jiao became a test of courage in local festivals and celebrations.

Notably, wrestling in this era began to transition from purely militarized forms to those with symbolic and ethical meanings—valuing control over domination, skill over brute force.

This period also seeded the philosophical underpinnings that would blossom later in neo-Confucian and Daoist interpretations of martial grappling—where yielding, balance, and internal control gained deeper meaning.

From Imperial Arts to Regional Pillars: Consolidation in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties

Mongolian Integration and Yuan Dynasty Expansion

The Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), established by the Mongols, marked a transformative chapter in the development of Shuai Jiao. Mongol wrestling traditions, particularly Bökh, were not only embraced by the ruling class but actively merged with earlier Han Chinese grappling systems. This fusion solidified the martial roots of Shuai Jiao and set the stage for regional diversification.

Key developments:

- Bökh’s emphasis on raw strength and upright posture complemented the balance-focused techniques of Han-style Jiao Li.

- Wrestlers were elevated to elite status, often employed as royal guards or instructors in military academies.

- The term Shuai Jiao began to replace Jiao Li in popular use, marking a linguistic and technical shift.

Note: In this period, the formal term “Shuai Jiao” gained widespread recognition, denoting a hybridized yet systematized approach to Chinese wrestling.

This was not merely a technical merger but a cultural one. Nomadic and sedentary worldviews fused in the martial arts sphere, reflected in Shuai Jiao’s philosophy of adaptability and control under pressure.

The Ming Dynasty’s Provincial Framework

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) brought a return to Han rule and, with it, a restructuring of martial institutions. Shuai Jiao was absorbed into the framework of military training academies (Wuying Dian) and regional militias.

Under Ming administration:

- Provincial schools of Shuai Jiao were established to train soldiers and palace guards.

- Wrestlers were often required to master specific regional variants based on the needs of local terrain and tactics.

- Official manuals began to appear, outlining sets of techniques categorized by objective (e.g., throws, locks, counters).

This period saw the formation of distinctive regional styles, which later solidified into formal lineages. Shuai Jiao began to divide along geographic lines—not as fragmentation, but as structured specialization.

Qing Dynasty Patronage and the Birth of Classical Styles

The Qing dynasty (1644–1912), ruled by the Manchu elite, preserved and refined many Ming martial traditions. At the imperial court, Shuai Jiao enjoyed privileged status as both a combat discipline and performance art. It was here that systematic transmission and stylistic crystallization occurred.

Major court-influenced lineages emerged:

- Manchurian Court Style (Baoding Shuai Jiao): Refined and ceremonial, often practiced by palace guards.

- Tianjin Shuai Jiao: Aggressive and straightforward, with an emphasis on practical throws.

- Beijing Shuai Jiao: Known for elegance, balance, and transitional techniques.

Elite instructors such as Shan Pu Ying wrestlers served as personal trainers for royal households and high-ranking officials.

Master Zhang Fengyan and Master Liu Baichuan were pivotal figures during the late Qing, codifying curriculum and opening the art to broader teaching formats while maintaining its aristocratic roots.

Lineage Formation and Technical Canonization

Clan Transmission and Secret Lineages

As the Qing period progressed, Shuai Jiao moved beyond the palace and military institutions into the hands of civilian practitioners and martial clans. Families began to pass down Shuai Jiao knowledge privately, sometimes within tightly guarded traditions. This development cultivated diverse technical vocabularies, rituals, and pedagogies.

Characteristics of clan-based Shuai Jiao:

- Oral transmission combined with mnemonic rhymes

- Emphasis on character development and family loyalty

- Secret techniques reserved for inner-circle students

In many cases, these clan styles would later form the backbone of modern lineages, especially during the Republican period.

The Rise of Public Teachers and Civil Schools

By the late 19th century, societal shifts—urbanization, literacy, the decline of Qing authority—allowed Shuai Jiao to enter the public teaching sphere. Masters began offering instruction outside military or court settings, creating a semi-formal educational structure.

Prominent teachers of this transition included:

- Chang Dongsheng (常东升): A national champion who later played a key role in standardizing techniques across regions.

- Li Baoru: Known for spreading Tianjin-style Shuai Jiao and developing accessible curricula for civilians.

Schools became more systematized:

- Curriculum divided into foundational drills, fixed forms, and free sparring

- Uniforms and ranking structures began to appear

- Names of techniques were formalized, including standardized terminology for grips, stances, and falls

This movement laid the groundwork for the Republican-era academies and future integration into modern martial arts institutions.

Philosophical Infusion and Interdisciplinary Exchange

During the late Qing and early Republican periods, Shuai Jiao increasingly absorbed philosophical elements from Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, emphasizing ethical conduct, self-mastery, and internal balance. Teachers began to frame Shuai Jiao not only as a method of self-defense but also as a path to personal cultivation.

This philosophical infusion came alongside interaction with other Chinese martial arts:

- Exchanges with Xingyiquan and Baguazhang led to cross-pollination of footwork and energy manipulation

- Daoist principles inspired internal variations, focusing on breath control and non-resistance

- Some schools integrated Shuai Jiao as a grappling component within a broader striking system

These developments did not dilute Shuai Jiao but rather enriched its depth, allowing it to endure periods of cultural transition and political upheaval.

National Identity, Standardization, and Institutionalization

Republican Reforms and Martial Nationalism

The early 20th century was a turbulent period in Chinese history, yet it played a critical role in shaping modern Shuai Jiao. After the fall of the Qing dynasty, the Republic of China sought to redefine national identity through physical culture and martial arts. Shuai Jiao was promoted as a native martial tradition that could strengthen citizens and instill patriotism.

Key developments:

- National martial arts events included Shuai Jiao alongside striking arts like Changquan and Taijiquan.

- Prominent masters such as Chang Dongsheng emerged, representing Shuai Jiao in military academies and national competitions.

- Shuai Jiao was incorporated into the curriculum of the Central Guoshu Institute (est. 1928), marking its entry into modern institutional frameworks.

The Guoshu movement aimed to unify Chinese martial arts under state guidance, reinforcing Shuai Jiao’s status as a legitimate and essential discipline.

During the Sino-Japanese War and civil conflict, Shuai Jiao continued to be practiced within military and police units. Though sometimes overshadowed by more visible striking arts, its utilitarian grappling made it indispensable in real-world combat settings.

People’s Republic and the Shift Toward Sport

After 1949, the establishment of the People’s Republic of China brought sweeping changes to all aspects of traditional culture, including martial arts. Shuai Jiao was reframed as a physical education discipline under state control, with an emphasis on safety, athleticism, and performance.

Transformations during this era:

- Shuai Jiao competitions were standardized with rulesets, weight classes, and safety equipment.

- Training methods were codified and published through state-sponsored manuals and physical education curricula.

- The Beijing Physical Education Institute and other government bodies played a role in professionalizing instruction.

This shift was not without tension. Traditionalists resisted the sportification of Shuai Jiao, fearing the loss of philosophical depth and combat practicality. Still, the sport form enabled mass participation and preserved visibility during periods when many other martial traditions were suppressed or discouraged.

Institutional Growth and National Recognition

From the 1980s onward, Shuai Jiao experienced a state-supported resurgence. With China reopening to the world and renewing interest in traditional culture, efforts were made to elevate Shuai Jiao both at home and abroad.

National structures included:

- The Chinese Shuai Jiao Association, responsible for organizing tournaments and certifying coaches.

- Integration of Shuai Jiao into university-level martial arts programs and military police training academies.

- Government-sanctioned demonstrations in international festivals, often paired with Wushu performances.

Despite competition from globally dominant combat sports (like Judo and Wrestling), Shuai Jiao retained a niche position as a cultural heritage art form with official backing.

Diaspora, Hybridization, and Global Adaptation

Masters Abroad and the First Overseas Schools

Shuai Jiao’s global journey began with the migration of Chinese masters during the mid-20th century. Political upheaval, war, and economic shifts led many instructors to relocate, especially to Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia, and later to North America and Europe.

Notable figures include:

- Chang Dongsheng, who taught extensively in Taiwan and helped institutionalize the art within military and police forces there.

- David Lin and Shuai Jiao Federation pioneers who established dojos in the United States.

- Wang Wenyong, instrumental in spreading Shuai Jiao to France and Italy.

In these new environments, Shuai Jiao often adapted to local demands. Some schools maintained traditional rituals and oral lineages, while others integrated modern athletic standards to appeal to younger students.

By the late 20th century, Shuai Jiao had a presence in more than 25 countries, each with its own approach to lineage, certification, and integration.

Interaction with Other Grappling Arts

Outside of China, Shuai Jiao did not exist in isolation. Its practitioners encountered and exchanged knowledge with a wide range of grappling traditions, including:

- Judo in Japan and the West

- Greco-Roman and Freestyle Wrestling in Olympic circles

- Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Sambo in MMA gyms and hybrid training centers

This led to the emergence of fusion schools and experimental formats, where Shuai Jiao throws were combined with ground control techniques from other arts. While purists viewed this as dilution, many saw it as evolution—a means to ensure relevance in contemporary martial practice.

Hybrid competitions also emerged, where Shuai Jiao stylists entered open grappling events, testing their systems against global opponents.

Digital Era, Online Teaching, and Cultural Revivalism

The rise of the internet and digital media in the 21st century significantly altered the way Shuai Jiao was taught, perceived, and practiced globally. Online platforms enabled international students to access rare training footage, purchase instructional material, and even attend virtual seminars with established masters.

Key trends:

- Online repositories for Shuai Jiao texts, oral histories, and video tutorials

- Social media promotion by younger athletes highlighting traditional and competitive Shuai Jiao

- Livestreamed matches and instructional Zoom sessions, especially during COVID-19 lockdowns

Parallel to digital expansion, a revivalist movement has gained momentum within China and abroad. This includes:

- Reintroduction of philosophical components rooted in Confucian and Daoist ethics

- Emphasis on nei gong (internal work) and martial etiquette in traditional schools

- Efforts to have Shuai Jiao recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage

Today, Shuai Jiao stands at the crossroads of tradition and transformation—rooted in thousands of years of history, yet evolving through new media, intercultural exchange, and a global generation of practitioners eager to preserve and adapt its legacy.

Summary Reflection:

From its battlefield and ritual origins to its modern incarnations as both sport and heritage, Shuai Jiao embodies the resilience and adaptability of Chinese martial culture. Across dynasties, ideologies, and continents, it has retained its core: the balance of strength, skill, and discipline in the art of the throw.