Urban Violence and Maritime Roots

Street Brawling in Early Modern France

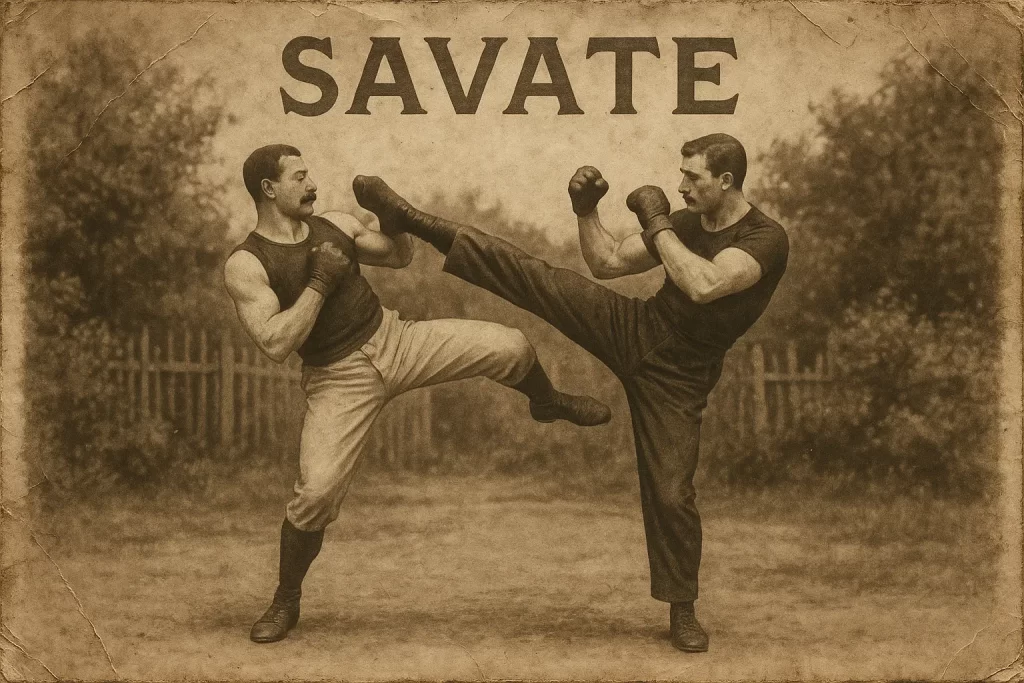

Savate did not emerge from temples or military academies, but from the grimy streets and chaotic ports of France between the 17th and 19th centuries. In major cities like Paris, Marseille, and Lyon, daily life for the lower classes was often turbulent, and street fighting became a cultural phenomenon. Local youths, workers, and sailors developed unarmed techniques for self-defense, typically involving slaps, open-hand strikes, kicks, and even improvised weapons.

The term savate, originally meaning an old shoe, reflected the brutal, unsophisticated kicking methods common in these early street encounters. Fights were as much about bravado and public status as self-preservation, and brawling styles varied significantly between regions. The early Parisian variant emphasized balance and upright posture, while southern styles—especially in Marseille—featured more acrobatic footwork influenced by seafarers’ mobility on ships.

Note: These regional variations later played a crucial role in the formal codification of Savate into a martial art.

Marseille’s Port Culture and Chausson

Marseille’s bustling harbor was a melting pot of cultural exchange, hosting merchants and sailors from Italy, Spain, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire. In this cosmopolitan crucible, a distinct kicking art known as Chausson (meaning slipper) began to take form. It focused on precise, elegant foot strikes and was practiced barefoot or in soft footwear, in stark contrast to the heavier street-style savate of the north.

Chausson was influenced by:

- Moorish and Berber kicking styles brought through North African sailors

- Italian fencing, particularly the emphasis on distance and timing

- French dance movements, with parallels drawn between ballet footwork and Chausson’s flowing kicks

Despite its sophistication, Chausson was still a practical self-defense method used in street altercations and dockside confrontations. Its development marks a critical divergence within the broader Savate tradition.

The Role of Naval and Merchant Seamen

French sailors traveling through the Mediterranean and Atlantic had ample exposure to foreign fighting styles. These influences—particularly from English boxing, Spanish foot-fighting, and North African martial traditions—were absorbed and adapted into local customs upon the sailors’ return.

Notably, Marseille’s sea-going culture facilitated:

- Transmission of English pugilism (early boxing), which later merged with Savate hand strikes

- Adoption of mobile footwork for narrow ship decks

- Cultural acceptance of hybrid fighting techniques, unconstrained by noble or academic codes

By the early 19th century, sailors and dockworkers formed a key demographic in propagating and evolving these unarmed techniques, setting the stage for their urban spread and eventual formalization.

Codification and Cultural Shifts

From Street Thugs to Self-Defense Method

Savate’s early practitioners were often viewed with suspicion by the bourgeoisie and police authorities. However, as violence among Parisian gangs (Apaches) rose in the 19th century, the need for a structured system of civilian self-defense grew. Reform-minded thinkers, some with military backgrounds, began collecting, documenting, and teaching these methods to create a more standardized discipline.

This transformation was driven by a few key trends:

- The Enlightenment emphasis on rational systems, order, and hygiene

- The growing urban middle class seeking non-lethal self-defense

- Police and military interest in equipping personnel with non-lethal arrest techniques

One early proponent of structured Savate was Michel Casseux, a former soldier and fencing instructor, who opened a salle in 1825 and sought to tame Savate’s rougher street image.

Michel Casseux and the Birth of Modern Savate

Known as le Pisseux, Michel Casseux is often credited with initiating Savate’s transition into a codified discipline. A veteran of Napoleonic military campaigns and a fencing teacher, he established one of the first formal training halls for Savate in Paris.

His contributions include:

- Banning headbutts, gouging, and other brutal elements from his curriculum

- Introducing controlled sparring and technical precision

- Combining Savate kicks with English boxing-style punches

Casseux’s influence helped Savate gain respectability among the middle and upper classes. Though not yet a fully codified martial art, it had begun its transformation from street practice to structured method.

Historical Note: Casseux’s legacy would later be advanced by Charles Lecour, who would finalize the integration of English boxing techniques into Savate, but his impact lies beyond the scope of this early period.

Paris as a Cultural Incubator

In the early 19th century, Paris was undergoing rapid transformation—culturally, socially, and architecturally. The expansion of boulevards, new public spaces, and mass transportation systems coincided with the growth of popular entertainment, including circuses and demonstrations of physical prowess.

Within this environment:

- Savate demonstrations became a popular attraction at fairs and theaters

- Physical education, gymnastics, and fencing flourished alongside Savate

- Debates around masculinity, honor, and civilian self-defense found fertile ground

Parisian cafés and social clubs sometimes hosted informal Savate bouts, blending spectacle with sport. The city’s vibrant artistic and intellectual milieu created a platform for Savate to evolve not just as a physical discipline but as part of a broader conversation about personal agency and civility.

From Hybrid Combat to Codified Art

Charles Lecour and the English Boxing Influence

The true turning point in Savate’s evolution came through Charles Lecour (1808–1894), a student of Michel Casseux. Lecour recognized the limitations of Savate’s early emphasis on kicks alone and sought to refine the system by incorporating elements of English boxing, which had gained popularity in continental Europe by the mid-19th century.

After studying boxing with English expatriates, Lecour created a hybrid system that unified:

- French kicking techniques (from savate and chausson)

- English-style punching, guard positions, and footwork

- A standardized approach to combinations, distancing, and timing

Lecour’s style became known as Savate de Défense or Boxe Française, marking the formal birth of modern Savate as a structured art. He also introduced gloves, a regulated ring format, and a curriculum that could be taught systematically.

Historical Note: Lecour’s contributions formed the foundation of all subsequent Savate schools. His students would go on to influence both military and civilian instruction.

Early Training Halls and Teaching Lineages

The mid-19th century saw the rise of the first formal salles (training halls) in Paris and other major cities. These schools began to move away from Savate’s street-fighting origins and adopted a model similar to fencing or gymnastics academies. Uniforms were introduced, and etiquette, ranks, and technical progression began to emerge.

Notable lineages from this era include:

- Joseph Charlemont, a direct student of Lecour, who formalized much of Savate’s curriculum and terminology

- Louis Vignol, who helped establish Savate instruction within the French military context

- Hubert Leboucher, who bridged civilian and elite instruction through demonstrations and publications

These instructors wrote training manuals, introduced methodical drills, and shaped the structure of modern pedagogy in Savate. The art was no longer a rough trade of brawlers but a teachable discipline with roots in honor, agility, and control.

Terminology, Uniforms, and Technical Standards

By the late 19th century, the codification of Savate had reached a new level of precision. Terminology was standardized in French, with clearly defined names for:

- Striking techniques (e.g., chassé, fouetté, revers)

- Defensive maneuvers (esquive, blocage)

- Footwork patterns and guard positions

Uniforms were adapted from fencing attire, with fitted jackets and trousers to allow clear observation of movement. Footwear became a defining feature—Savate was one of the few martial arts to maintain its identity through the use of specialized shoes, which protected both the practitioner and the opponent while preserving the art’s distinctive kicking mechanics.

The introduction of these standards allowed for:

- Objective evaluation in instruction and demonstration

- Consistent lineage transmission across generations

- Clear differentiation from other emerging fighting systems

Expansion into Institutions and the Military

Military Adoption and National Identity

As France underwent political upheavals and wars in the 19th century—including the Franco-Prussian War and colonial expansion—there was renewed interest in developing native combat systems that reflected national pride and utility. Savate was increasingly viewed as a suitable method for military training, especially for close-quarters combat and physical conditioning.

The French military began incorporating Savate elements into training programs for:

- Infantry units and the Gendarmerie

- Colonial troops operating in North Africa and Indochina

- Naval personnel, who benefited from the system’s mobile footwork

By the 1880s, Savate had become part of a broader movement to foster physical culture (culture physique) in the army, aligning it with fencing, gymnastics, and wrestling.

Note: Joseph Charlemont was a pivotal figure in establishing Savate’s military credentials, thanks to his instructional role and his widely read treatises.

Schools for the Bourgeoisie and Academic Circles

Parallel to its military integration, Savate also found a place among the urban bourgeoisie and intellectual circles. With the rise of leisure culture and the ideal of the honnête homme (refined gentleman), many Parisian academies and clubs began offering Savate as part of physical education programs.

Key developments included:

- The establishment of Savate courses at law schools and civil service academies

- Private instruction for aristocrats and urban elites

- Integration with fencing and dance schools, particularly in Paris and Lyon

Instructors like Joseph Charlemont and later his son Charles Charlemont became renowned not only as fighters but as educators who taught discipline, timing, and control—qualities in line with the moral expectations of the time.

Savate thus evolved into a respectable pursuit, balancing athletic challenge with cultural refinement.

Resistance and Rival Currents

Despite the formalization process, some factions resisted Savate’s academic trajectory. Traditionalists and street practitioners argued that the art was losing its raw effectiveness. In cities like Marseille, where chausson retained its local identity, hybrid versions persisted with less emphasis on conformity and more on improvisation.

Key tensions emerged:

- Structured vs. instinctive practice

- Codified terminology vs. regional slang

- Urban bourgeois identity vs. working-class roots

These rival currents did not fracture the system but added depth and diversity to its expression. In fact, the eventual recognition of multiple styles within Savate (e.g., Savate de Rue, Savate Forme, Savate Défense) would owe much to this internal dialogue between formality and tradition.

International Expansion and Institutional Growth

The Charlemont Legacy and Early Global Bridges

At the dawn of the 20th century, Charles Charlemont—son of Joseph Charlemont—was instrumental in promoting Savate beyond French borders. A celebrated champion and teacher, he conducted demonstrations across Europe and influenced early martial art exchanges with England, Belgium, and parts of Eastern Europe. His work helped position Savate not only as a French discipline but as a refined European martial art.

During this period, the art gained visibility through:

- International exhibitions and staged matches

- Publications and instructional manuals translated into other languages

- A small but growing circle of foreign practitioners trained directly in France

However, despite these initial steps, Savate’s global expansion remained limited, overshadowed by the rise of judo, boxing, and other combat sports with more aggressive international marketing and institutional backing.

Note: The Charlemont family’s role provided the necessary pedagogical credibility to seed Savate in foreign cultural and sporting institutions.

The Federation Era and Formal Recognition

Post-World War II, France underwent significant efforts to organize and promote its indigenous martial arts. In 1945, the Fédération Française de Boxe Française et de Savate was established, marking a decisive moment in the art’s institutional modernization. This national body aimed to standardize competition, promote Savate education, and unify fragmented lineages.

Key outcomes included:

- Creation of official coaching diplomas and training curriculums

- Establishment of national championships and ranking systems

- Integration of Savate into national sports federations and physical education programs

Savate was now officially recognized as a sport under the French Ministry of Sport. This structure provided a launchpad for international collaborations and future Olympic lobbying efforts, even as Savate continued to define itself culturally as more than just a sport.

Global Diaspora and Cultural Exchange

Savate’s true globalization began in the late 20th century as French masters emigrated, foreign students trained in France, and global interest in martial arts surged. By the 1980s and 1990s, Savate schools had been established in countries such as:

- Canada, Belgium, and Switzerland (with strong French linguistic ties)

- Brazil and Argentina (through Franco-European cultural exchange)

- The United States, Australia, and Japan (via interest in hybrid and European systems)

These communities varied in their approach. Some maintained a traditional lineage model closely tied to the French federation, while others adapted Savate into eclectic combat sports or self-defense curricula.

Insight: This period marked Savate’s emergence not just as a French heritage discipline, but as a global martial art with regionally adapted expressions and decentralized growth.

Modern Challenges and Revivals

Tension Between Tradition and Innovation

As Savate reached new audiences, debates intensified over the balance between preservation and progress. Traditionalists emphasized lineage purity, adherence to French terminology, and the philosophical roots of Savate as a gentleman’s art. Modernists pushed for innovation, sportification, and fusion with other martial systems.

These internal dynamics manifested in:

- Diverging curricula between traditional Savate de Défense and competitive Savate Boxe Française

- The emergence of Savate Forme, a non-combative fitness variant designed for broader audiences

- Grassroots calls for greater recognition of Savate de Rue (street Savate), which emphasized the art’s original urban context

In many ways, this cultural tension mirrors parallel debates in other martial arts systems—from karate to kung fu—where questions of authenticity, commercialism, and evolution remain unresolved.

The Internet, Instructional Media, and Digital Lineages

The digital revolution of the 2000s transformed the way Savate was taught, transmitted, and discussed. Online videos, forums, and social media enabled practitioners around the world to:

- Access rare footage and historical demonstrations

- Study under French masters through virtual seminars and distance learning

- Cross-train and compare techniques with other martial arts communities

New generations of students increasingly encountered Savate through YouTube channels, hybrid fitness platforms, and influencer-driven instruction. While this democratized access, it also raised concerns over dilution, misrepresentation, and the erosion of formal instructor-student relationships.

Contemporary Note: Many French instructors began developing structured online certification programs in response, seeking to preserve standards in a digital age.

Revivalist Movements and Return to Roots

Despite its modern evolutions, Savate has also seen revivalist efforts aiming to reconnect the art with its origins. These movements focus on:

- Reintroducing historical chausson techniques and maritime footwork

- Teaching self-defense in urban scenarios reminiscent of 19th-century France

- Highlighting the sociocultural roots of Savate in working-class and port city traditions

Several French and international schools have started offering seminars that explore the pre-Casseux and pre-Lecour phases of Savate, including period clothing, reconstructed techniques, and historical context.

These initiatives not only enrich the cultural identity of Savate but offer a broader narrative beyond the sporting arena—one that affirms its place in France’s urban history and global martial heritage.

Savate’s journey from Marseille’s docks to international dojos reflects both the adaptability and the complexity of martial traditions in the modern era. Its future likely lies in this dynamic interplay between deep roots and global reach.