Crossroads of Combat: Global Roots of Hybrid Fighting

Greco-Roman Foundations and the Legacy of Pankration

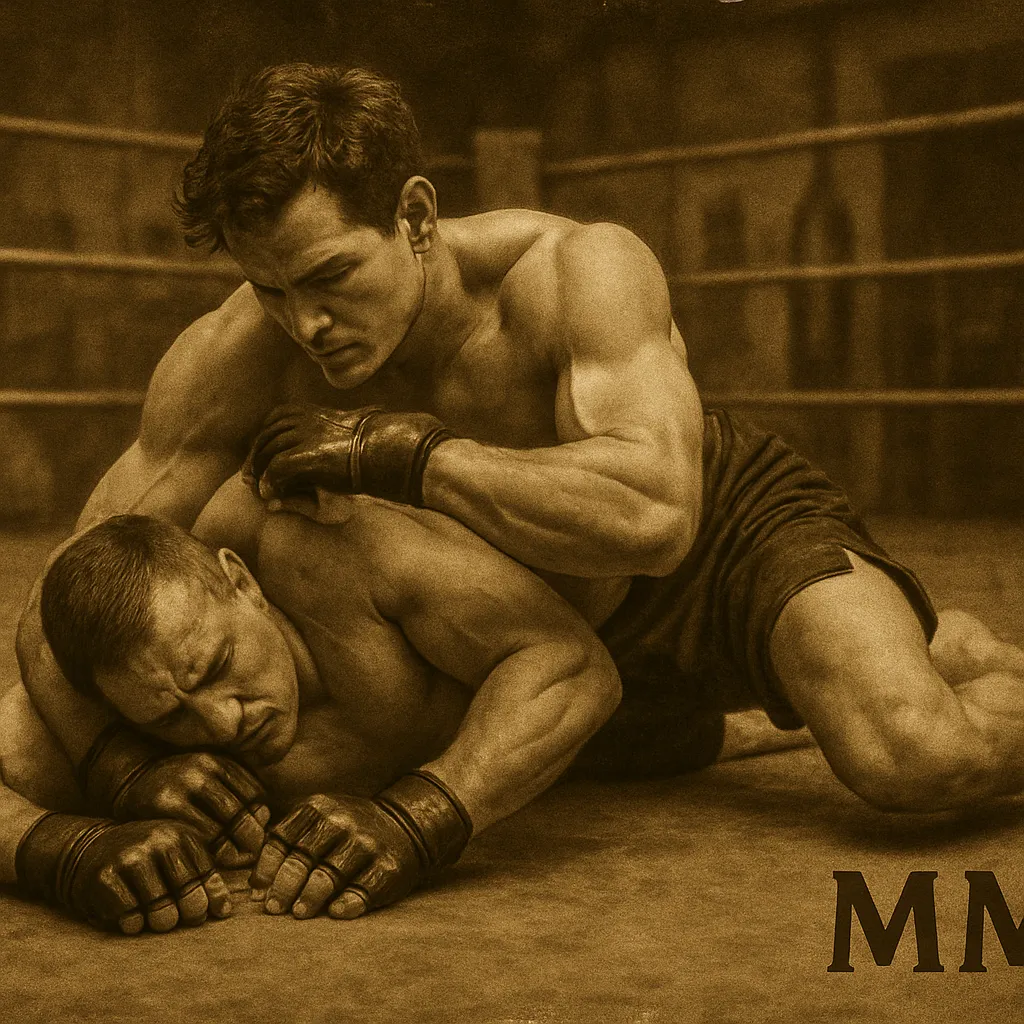

Long before the term Mixed Martial Arts existed, ancient civilizations practiced systems that blurred the boundaries between striking and grappling. Among the most influential was pankration, a brutal yet disciplined combat sport introduced into the Olympic Games in 648 BCE by the Greeks. Pankration merged boxing (pygmachia) with wrestling (palé), allowing a wide range of techniques except biting and eye-gouging. It reflected not only Greek athleticism but also a martial mindset shaped by inter-city warfare and mythological ideals of heroism.

Roman gladiatorial games absorbed these combat elements, adapting them to the spectacle of the Colosseum. Gladiators, trained in specialized ludi, often used a blend of techniques tailored to their weapon class or armor. While the Roman emphasis was more theatrical and fatal, the fusion of martial styles under one arena planted a psychological and structural seed for what would much later emerge as MMA.

Note: Although often sensationalized, Roman and Greek systems provided the first formal frameworks where hybridized unarmed combat was both institutionalized and popularized.

Cultural Exchange Through Conquest and Migration

As empires expanded, so did their martial knowledge. Alexander the Great’s campaigns brought Greek martial concepts deep into Central Asia, where they encountered Persian wrestling and Indian malla-yuddha. Later, trade routes such as the Silk Road became corridors for sharing fighting styles. Mongol incursions into Europe and the Middle East further disseminated close-combat tactics, including horseback grappling and battlefield submissions.

These exchanges didn’t produce MMA in any modern sense, but they initiated centuries of technical blending. In some cases, traditional arts adapted foreign elements into their curriculum; in others, regional rule sets preserved their distinctions but allowed hybrid tournaments or clan challenges.

Cultural diffusion of martial practices, especially in border regions, laid the groundwork for hybrid styles that could operate under multiple contexts—ritual, self-defense, and contest.

Indigenous Synthesis in Pre-Modern Societies

In regions like Southeast Asia, West Africa, and the Caucasus, local forms of hybridized combat emerged organically. Southeast Asian fighters combined striking and clinching in styles like Muay Boran or Lethwei; West African traditions such as Dambe and Laamb often fused ritual dance with wrestling and punching; Caucasian peoples practiced a mix of wrestling and striking with combat readiness in mind.

These systems were not merely martial but deeply woven into social and spiritual structures. Combat was a rite of passage, a celebration, and a means of justice. Although geographically distant, their converging principles—no separation between striking and grappling, emphasis on full-body training, and cultural embedding—echo the later ethos of MMA.

The 20th Century Emergence of MMA Precursors

Vale Tudo and the Brazilian Battlegrounds

In early 20th-century Brazil, carnival promoters and circuses began advertising vale tudo—no-holds-barred fights between different martial artists. This was less sport and more spectacle, but it brought martial ideologies into direct confrontation. The Gracie family, drawing from Japanese jujutsu and later jiu-jitsu, became central figures in this movement, challenging boxers, wrestlers, and capoeiristas to test their art’s supremacy.

Vale tudo wasn’t institutionalized, and its legality varied. But its gritty, rules-light matches mirrored many structural aspects of contemporary MMA—weight disparity, limited rules, and style-versus-style dynamics. These public spectacles set Brazil apart as a major incubator of full-contact, interdisciplinary combat.

Historical note: Carlson Gracie and his students later refined these confrontations into more codified systems, influencing MMA’s technical and cultural evolution.

Japanese Shoot-Style Wrestling and Early MMA Hybrids

Post-WWII Japan saw an explosion of interest in professional wrestling, but by the 1980s, promotions like UWF and Shooto began pushing beyond scripted matches. These so-called shoot-style organizations aimed to blend realistic wrestling with submissions and striking in a quasi-legitimate format. They blurred entertainment and combat, but also fostered real technical innovation.

Shooto, founded by Satoru Sayama in 1985, was one of the first structured combat systems to define itself explicitly as mixed-style fighting. It incorporated boxing, wrestling, and submission grappling under consistent training and competition rules. Although obscure in the West, Shooto laid the foundation for future organizations like Pride and UFC.

Japan’s early hybrid leagues were not just experimental but philosophically committed to realism, anticipating many of MMA’s later global norms.

American Toughman Contests and Cross-Disciplinary Combat

Meanwhile, in North America, regional Toughman contests and underground fight circuits in the 1970s and 1980s allowed untrained or semi-trained individuals from different martial backgrounds to clash in rudimentary rings. While these events were rarely safe or regulated, they demonstrated a growing public appetite for real, unscripted confrontations between boxing, karate, and wrestling.

The rise of Bruce Lee’s philosophy in the 1970s also fueled the idea of eclectic combat. His concept of Jeet Kune Do rejected traditional rigidity in favor of using what works—absorb what is useful, discard what is useless—a mantra that resonates with the MMA practitioner to this day.

Cultural shift: From Lee’s personal evolution to Toughman contests, the American scene began embracing function over form, helping set the cultural tone for MMA’s eventual arrival.

From Challenge Matches to Structured Training: Building MMA’s Foundations

Gracie Jiu-Jitsu and the Formalization of Vale Tudo Knowledge

The early Gracie family played a pivotal role in transforming vale tudo chaos into a recognizable martial lineage. Helio Gracie, in particular, is credited with adapting traditional judo-based techniques to suit smaller fighters, focusing on leverage, timing, and ground control. What emerged by the mid-20th century was more than a family tradition—it was a formalized system of instruction.

The Gracie academies in Rio de Janeiro began to implement:

- Rank structures with colored belts distinct from judo norms

- Defined curricula, including positional drills and sparring formats

- Challenge-based pedagogy, where real fights were used to verify progress

Gracie Jiu-Jitsu was not just a martial art but a teaching model. By codifying its approach, it laid the groundwork for replicable, transmittable training—a critical step toward MMA as a structured discipline.

Legacy note: Rolls Gracie later incorporated elements of wrestling and sambo, foreshadowing the mixed-method evolution of the Gracie system.

Shooto’s Technical Standardization and Coaching Framework

In Japan, Satoru Sayama’s creation of Shooto in the mid-1980s marked one of the first attempts to formalize an explicitly mixed combat system. Unlike vale tudo, Shooto was built from the ground up with structure in mind.

Key institutional innovations included:

- A ranking system based on competitive performance and technical proficiency

- An instructor licensing system, standardizing how coaches taught around Japan

- Regularized competition rules, balancing realism and safety for athlete development

Shooto’s model borrowed from wrestling, kickboxing, and jiu-jitsu, but synthesized them into a coherent, teachable system. Unlike previous systems that adapted to fights, Shooto adapted fights to fit pedagogical goals—a fundamental shift in MMA’s development.

Dojos, Camps, and the Shift Toward Integrated Training

As various fighters recognized the limits of single-discipline approaches, the late 1980s and early 1990s saw the emergence of integrated training environments. These were no longer traditional dojos but hybrid camps where striking, grappling, and clinch work were all taught under one roof.

Key early examples included:

- Brazilian Top Team (founded by Murilo Bustamante and others)

- Chute Boxe Academy, focused on aggressive striking blended with takedown defense

- Lion’s Den, established by Ken Shamrock in the US as a proto-MMA gym

These camps didn’t just train fighters—they began to produce generations of athletes under a defined ethos and curriculum. The shift from informal cross-training to camp-based instruction systems marked a new phase of institutional evolution.

Integrated camps began forming their own identities and lineages, with coaching trees that trace into modern MMA teams worldwide.

Codifying Philosophy and Pedagogy in a Fragmented Landscape

Jeet Kune Do’s Philosophical Influence on MMA Pedagogy

Though not an MMA system per se, Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do had a lasting impact on how fighters approached skill integration. Lee rejected stylistic orthodoxy, emphasizing adaptability, economy of motion, and personal expression in combat.

Jeet Kune Do introduced:

- Philosophical minimalism—discarding excess movement and ritual

- Interdisciplinary freedom—training across styles without tribal loyalty

- A mindset of realism, where theoretical purity yielded to practical outcomes

While Jeet Kune Do schools varied in rigor and lineage, the idea of cross-disciplinary inquiry became a pedagogical principle in MMA. Coaches began teaching students how to learn, not just what to memorize.

Bruce Lee’s conceptual legacy made MMA possible not just technically, but intellectually.

Naming Conventions and Curriculum Articulation

As schools and gyms began to formalize instruction, they needed shared language. The result was a gradual emergence of naming conventions that helped organize MMA knowledge. Though lacking a global standard, several terms became widely used:

- Striking range vs. clinch range vs. ground range

- Positions like guard, mount, and side control became technical anchors

- Hybrid drills (e.g., wall work, cage wrestling) were introduced as distinct modules

This vocabulary allowed coaches to build cohesive lesson plans and share knowledge across gyms. The evolution of shared terms also contributed to the visibility and legitimacy of MMA as a teachable system, not just a collection of tactics.

Resistance and Reform Among Traditionalists

The rise of MMA pedagogy did not occur without friction. Traditional martial artists—particularly those from karate, kung fu, and taekwondo lineages—often viewed MMA as crude or dishonorable. In response, some traditional schools reasserted ritual, while others embraced reform.

Two major responses emerged:

- Isolationist traditionalism, preserving classical forms and eschewing MMA

- Absorption schools, which modernized their syllabi to include ground work, clinch drills, or conditioning derived from MMA

Examples of the latter include certain karate jutsu clubs in Japan and hybrid kung fu sanda academies in China. In some cases, cross-pollination occurred through individual students leaving traditional arts for MMA and then returning to reform their origins.

The institutional story of MMA is also the story of conflict and adaptation. While some resisted, others redefined themselves through the challenge MMA posed.

From Regional Scenes to Worldwide Infrastructure

The Rise of Global Promotions and Organizational Authority

By the 1990s, MMA began shifting from underground contests and regional circuits into formalized global organizations. The founding of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) in 1993 in the United States catalyzed this shift. Though initially promoted as a spectacle without rules, UFC evolved into a legitimate sports organization with athletic commissions, standardized regulations, and media broadcasting.

This period also saw the emergence of:

- PRIDE Fighting Championships in Japan, which maintained theatricality but fostered elite-level competition

- Shooto’s global expansion, with affiliates and rule sets in Europe and South America

- Pancrase and Rings, which introduced hybrid formats and emphasized submission proficiency

These promotions institutionalized MMA on a global scale, shifting it from a loosely connected practice into an industry with governance, athlete contracts, and international matchmaking.

Note: The global organizational structure mirrored that of boxing and wrestling but introduced cross-disciplinary matchups as a core feature.

Spread Through Diaspora, Migration, and Martial Tourism

The international spread of MMA owes much to the movement of people. Brazilian fighters relocated to the United States and Europe, bringing with them not just techniques but teaching models. Meanwhile, Japanese trainers mentored athletes across Southeast Asia and Australasia.

Factors accelerating this process included:

- Martial arts tourism, where practitioners traveled to train in Brazil, Thailand, or Japan

- Post-Cold War migration patterns, opening Eastern European and Central Asian talent pools

- Return migration, where fighters brought MMA knowledge back to their home countries

From Dagestan to Dublin, the global map of MMA shifted rapidly as regional gyms absorbed and adapted to the sport. Local fighters began achieving international recognition, accelerating the localization of global MMA infrastructure.

Federations, Gyms, and the New Institutional Landscape

By the 2000s, MMA had evolved beyond independent promotions into an ecosystem of gyms, governing bodies, and educational systems. Federations such as IMMAF (International Mixed Martial Arts Federation) emerged to promote amateur competition and safety regulations.

Elite MMA gyms—many evolved from earlier vale tudo or wrestling clubs—transformed into international brands:

- American Top Team, with affiliates across North and South America

- Jackson Wink MMA, known for its strategic training systems

- Tiger Muay Thai, combining striking roots with modern MMA infrastructure

These institutions formalized coaching certifications, athlete development pipelines, and global talent scouting. MMA no longer relied on isolated genius or tribal systems—it had become a teachable, exportable, and reproducible framework.

Gyms became cultural ambassadors, shaping local fight culture while interfacing with global trends.

Digital Age, Commercial Growth, and Philosophical Recalibration

Mass Media and the Transformation of Fighter Identity

Television, film, and eventually streaming platforms revolutionized how MMA was consumed. Shows like The Ultimate Fighter turned athletes into household names, while viral knockouts and documentary series gave fans direct access to fighter journeys.

This shift influenced:

- Athlete branding, as fighters cultivated public personas alongside skillsets

- Cross-cultural fandom, with viewers from multiple continents following shared leagues

- Commercial endorsements, transforming fighters into influencers and entrepreneurs

Fighter identity, once forged in gritty gyms, became partially shaped by camera angles, interviews, and Instagram metrics.

Cultural tension: Fighters now straddled roles—athlete, brand, artist—often leading to internal conflict about purity vs. performance.

Online Learning, Remote Coaching, and Tactical Hybridization

The digital revolution opened unprecedented access to MMA knowledge. Instructional videos, seminars, and coaching platforms broke geographical boundaries. A student in Nairobi could now study guard retention from a Brazilian coach or learn wrestling chain drills from an American collegiate champion.

Modern MMA pedagogy began including:

- Online curriculums, like BJJ Fanatics or Dynamic Striking

- Remote sparring analysis, via video submission and real-time coaching

- Live-streamed seminars, reaching thousands simultaneously

This democratization of access accelerated hybridization. Fighters could now mix judo takedowns with Dutch striking drills and American wrestling strategy—all without leaving their country.

MMA became not just a sport of the gym, but of the algorithm.

Tradition Revisited: Cultural Revival Within MMA

Despite its globalized form, modern MMA has seen increasing interest in returning to roots. Fighters and coaches explore ancestral systems, reviving techniques and rituals once considered obsolete. Examples include:

- Dagestani fighters integrating traditional kuresh wrestling styles into global competition

- BJJ schools reintroducing self-defense curricula inspired by Helio Gracie’s early philosophy

- Muay Thai-influenced camps reasserting ceremonial elements such as the wai khru ritual in MMA walkouts

At the same time, some MMA practitioners critique the sport’s commodification, seeking a reconnection with martial values—humility, discipline, personal growth—that echo older traditions.

Philosophical shift: From cage spectacle to soul practice, some parts of MMA are circling back to their spiritual lineage.