Cultural Crossroads and the Roots of Innovation

The Sino-American Context of the 20th Century

Jeet Kune Do was not born in a vacuum. Its foundations were laid in a turbulent era marked by cultural intersections between East and West, especially the United States and China. Bruce Lee, the founder of Jeet Kune Do, stood at the nexus of this convergence. Born in San Francisco in 1940 to Cantonese opera performers and raised in post-war Hong Kong, Lee experienced firsthand the profound duality of traditional Chinese values and modern Western urban life.

This dual cultural exposure deeply shaped his philosophical orientation and later innovations. On one hand, he was steeped in Confucian respect for lineage and discipline; on the other, he encountered the individualism and pragmatism of American society. These dualities would come to define the ideological underpinnings of Jeet Kune Do.

Martial Arts Culture in Post-Qing China and Hong Kong

Following the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, Chinese martial arts began a transitional phase. Traditional systems like Wing Chun, Hung Gar, and Choy Li Fut saw renewed interest amid nationalist efforts to preserve Chinese identity during times of political fragmentation and colonial pressure.

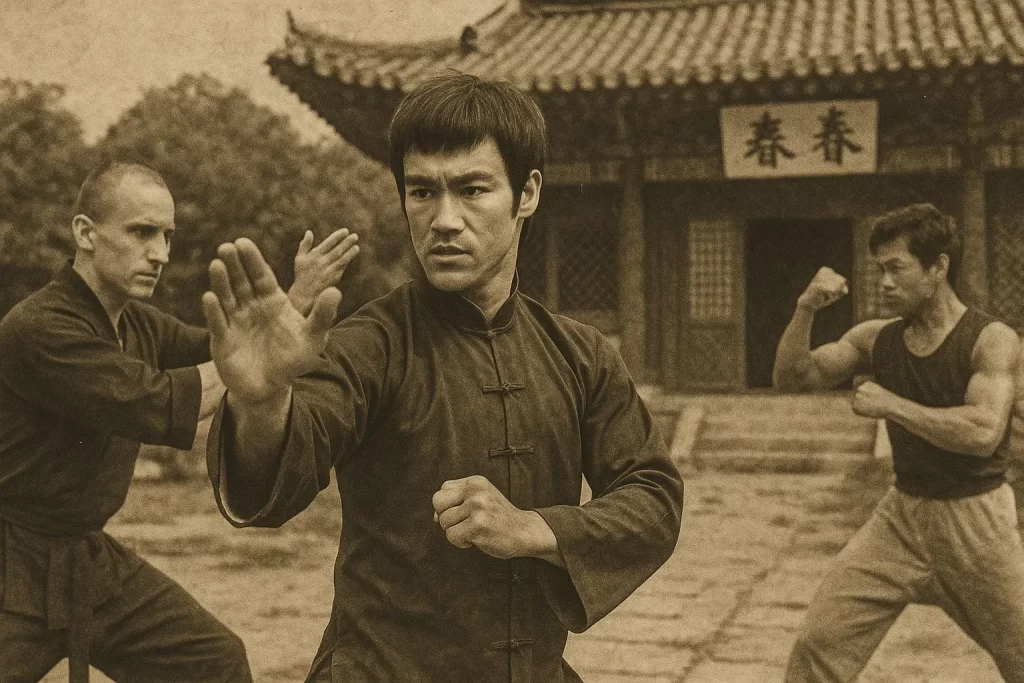

In Hong Kong, British colonial governance introduced Western education systems, boxing, and fencing to local youth. Simultaneously, urban martial arts lineages vied for legitimacy and students in cramped tenement rooftops and narrow alleys. Bruce Lee entered this arena as a teenager, training under Ip Man in Wing Chun—one of the few styles emphasizing close-quarters efficiency and directness, traits that would influence Jeet Kune Do’s later development.

Wing Chun’s emphasis on economy of motion, centerline theory, and sensitivity training (chi sao) created a technical and conceptual springboard for Lee’s eventual critique and transcendence of traditional styles.

Rise of Global Migration and Diaspora Identity

The mid-20th century saw a wave of Chinese emigration due to civil war, economic hardship, and colonial instability. Many Chinese communities formed in North America, where immigrants often faced racial prejudice, cultural displacement, and legal marginalization (e.g., the Chinese Exclusion Act in the U.S., repealed only in 1943).

For Chinese martial artists abroad, these challenges created both constraints and opportunities. Martial arts schools became not just training centers, but communal sanctuaries for cultural preservation and social identity. However, some traditionalists resisted teaching martial arts to non-Chinese students—an attitude Lee famously defied.

Lee’s own relocation to Seattle in 1959 at the age of 18 placed him directly in the midst of this transpacific identity tension. His early efforts to teach martial arts to a racially diverse student body would catalyze one of the most significant paradigm shifts in the history of hand-to-hand combat.

The Disruption of Tradition and Emergence of New Principles

Bruce Lee’s Reaction Against Fixed Systems

By the early 1960s, Bruce Lee had grown disillusioned with the rigidity of traditional martial arts. He viewed many systems as overly formalized, with set patterns (katas/forms) that, while beautiful in structure, were detached from the reality of combat. This criticism echoed broader movements of skepticism toward hierarchy and dogma emerging globally in post-war philosophy, including existentialist and pragmatist thought.

He began dismantling stylistic orthodoxy and instead favored adaptability, immediacy, and personal expression. He famously wrote, “Man, the living creature, the creating individual, is always more important than any established style or system.”

This philosophical shift marked the beginning of his development of Jun Fan Gung Fu (named after his Cantonese given name), which became the precursor to Jeet Kune Do. This transitional phase emphasized effective striking, speed drills, and flow, but was still rooted in a personal amalgamation of styles.

Influence of Western Combat Sports

During his time in the U.S., Bruce Lee was exposed to Western boxing, fencing, and wrestling—arts with a deeply different methodology than classical kung fu. American boxing, for instance, prioritized footwork, head movement, and dynamic rhythm. Fencing emphasized timing, distance, and linear attack—traits that deeply resonated with Lee’s evolving combat philosophy.

He adopted the fencing stance’s lead-hand emphasis and integrated boxing’s jab-cross mechanics into his repertoire. He began redefining stances, guard positions, and striking trajectories, departing from the rootedness of classical Chinese forms.

Moreover, Lee sparred with athletes from diverse disciplines, including karateka, judoka, and taekwondo practitioners. These experiences reinforced his belief that no single system could prepare one for the chaotic nature of real combat—and that martial knowledge must be continuously tested and refined.

Philosophical Influences and the Taoist Framework

While Lee distanced himself from martial traditionalism, he deeply embraced classical Chinese philosophy—particularly Taoism and Zen Buddhism—as frameworks for understanding combat, perception, and personal growth. He drew heavily from texts like the Tao Te Ching, emphasizing principles such as:

- Wu wei (effortless action)

- Ziran (naturalness)

- Yin and yang (duality and balance)

These ideas were not merely aesthetic additions but core tenets that influenced how he conceptualized motion, resistance, and timing. His idea of “using no way as way” and “having no limitation as limitation” synthesized Taoist fluidity with the existential freedom of Western thought.

In this context, Jeet Kune Do’s embryonic form emerged not just as a martial method, but as a philosophical rebellion against fixed identity, cultural purism, and mechanical repetition.

The System Takes Form: From Concept to Curriculum

Jun Fan Gung Fu Schools and Their Framework

Bruce Lee’s initial efforts to teach his evolving martial ideas began with the founding of the Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute in Seattle in 1963. While still grounded in Wing Chun mechanics, the school quickly departed from rigid tradition, incorporating Western boxing, fencing, and individualized drills. This marked the beginning of a formalized curriculum, albeit one built on dynamic adaptation.

The Seattle school became the prototype for two more branches:

- Oakland School, opened with James Yimm Lee, emphasized power and conditioning.

- Los Angeles Chinatown School, opened in 1967, became the philosophical heart of Jeet Kune Do and featured elite students like Dan Inosanto, Ted Wong, and Jerry Poteet.

Each school followed Bruce Lee’s personal philosophy of growth through experience. The structure was intentionally fluid:

- No kata or fixed routines

- Emphasis on sparring and improvisation

- Conditioning as integral to skill development

- Techniques adapted based on the student’s attributes

Lee taught that martial art was a process, not a product. While a curriculum existed, it was constantly being challenged and reshaped by application.

Naming the Way: Birth of Jeet Kune Do

In 1967, Bruce Lee officially coined the term Jeet Kune Do (The Way of the Intercepting Fist). The naming marked a turning point in the art’s institutional identity. Though Lee would later resist the ossification of any “style,” naming the system gave students a conceptual anchor.

The name signaled three important principles:

- Jeet (to intercept) reflects the strategic essence—interrupting the opponent’s intent

- Kune (fist) refers to striking as a primary means of expression

- Do (way or path) acknowledges a philosophical journey rather than just a set of techniques

Lee emphasized that Jeet Kune Do was not a style but a process of self-actualization. This paradox created challenges for institutionalization: how does one teach a system whose core tenet is the rejection of systems?

Despite the contradiction, the name gained traction, especially as Lee’s fame spread. It was during this era that training notes, diagrams, and private lessons started to evolve into an informal but influential pedagogical body.

Key Disciples and the Seeds of Divergence

While Bruce Lee’s own teaching career was brief—cut short by his untimely death in 1973—his legacy was carried forward by a core group of trusted students, each of whom interpreted his lessons through their own lens.

Some of the most influential early figures include:

- Dan Inosanto, known for cataloging Lee’s drills and methods, and fusing them with Filipino martial arts

- Ted Wong, a purist who trained solely under Lee in the later years and resisted hybridization

- Taky Kimura, Lee’s close friend and assistant instructor in Seattle, focused on preserving Jun Fan Gung Fu

- Jesse Glover, Lee’s first student, who emphasized simplicity and street realism over formal progression

This period planted the seeds for future divergence in JKD’s lineage. Each disciple preserved part of Lee’s vision—but no single successor could encompass its entirety.

Divergence and Doctrinal Debate

Jeet Kune Do Concepts vs. Original JKD

By the late 1970s and into the 1980s, Jeet Kune Do had split into two philosophical camps:

- Original Jeet Kune Do (OJKD): Focused on preserving Bruce Lee’s last-phase teachings, particularly the Los Angeles Chinatown curriculum. Proponents like Ted Wong and Jerry Poteet emphasized direct transmission.

- Jeet Kune Do Concepts (JKD Concepts): Championed by Dan Inosanto and others, this approach viewed JKD as an evolving framework open to cross-training and integration with other arts (e.g., Muay Thai, Filipino Kali, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu).

Key differences:

| Element | Original JKD | JKD Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Curriculum | Fixed around Lee’s final teachings | Open to continuous evolution |

| Emphasis | Purity and simplicity | Diversity and adaptability |

| Influences allowed | Wing Chun, fencing, boxing only | Multiple arts integrated |

| Core figures | Ted Wong, Jerry Poteet | Dan Inosanto, Paul Vunak |

These differences caused tension within the JKD community. Originalists feared dilution and loss of identity, while the Concepts school viewed strict preservation as antithetical to Lee’s philosophy.

Formalization Through Seminars and Organizations

As Bruce Lee’s fame grew posthumously, so too did the interest in his martial philosophy. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, seminars became the primary mode of JKD transmission. Figures like Dan Inosanto traveled worldwide, offering workshops and instructor certifications.

This phase saw the emergence of organizations such as:

- Inosanto Academy of Martial Arts (Los Angeles)

- Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Nucleus

- Bruce Lee Foundation, established by Lee’s family

These bodies contributed to a more structured transmission model, with syllabi, certification paths, and affiliate schools. However, they also introduced complexity—creating an ecosystem where not all JKD instructors agreed on what “authentic” meant.

Preservation vs. Innovation

The institutionalization of Jeet Kune Do inevitably sparked debate about the boundaries of legitimacy. Was JKD a museum of Bruce Lee’s mind—or a living laboratory for martial evolution?

Some practitioners, particularly in the Original JKD line, became archivists—meticulously preserving Lee’s writings, audio, and training routines. Others forged ahead, blending JKD with:

- Filipino weapons systems

- Mixed martial arts

- Combat sports and military combatives

This debate remains unresolved. Jeet Kune Do never became a rigid orthodoxy precisely because its founder warned against dogma. Yet that same openness created a lineage that continues to redefine itself—anchored to Lee’s vision, but never confined by it.

From Underground Art to Global Legacy

Posthumous Popularity and the Role of Mass Media

Bruce Lee’s untimely death in 1973 ignited a global wave of interest in his life and ideas. His films—Enter the Dragon, The Way of the Dragon, and Fist of Fury—reached international audiences and introduced Jeet Kune Do not as a codified system, but as a martial philosophy rooted in cinematic charisma and kinetic power.

Mass media played a transformative role:

- Martial arts magazines published Lee’s writings and training notes

- Documentaries and biographies reframed JKD as a cultural symbol of resistance and individuality

- Hollywood tributes sustained interest in Lee’s methods well into the 1990s

Jeet Kune Do became a household name, but this visibility also abstracted it from its training roots. In many cases, JKD was interpreted as an ethos rather than a method—fueling both romanticization and misrepresentation.

Expansion Through Students and Global Seminars

The global spread of Jeet Kune Do during the late 20th century was driven primarily by Bruce Lee’s direct students. By the 1980s and 1990s, many had established their own schools and certification programs around the world.

Key global contributors included:

- Dan Inosanto: conducted seminars in Europe, South America, and Southeast Asia

- Richard Bustillo: co-founded the IMB Academy, blending JKD with Filipino boxing and Muay Thai

- Tommy Carruthers (Scotland) and Chris Kent (USA): helped represent JKD in Europe and North America respectively

Training camps and weekend workshops made JKD accessible in regions far from its original roots. Itinerant instructors taught modular curricula, often blending JKD with Kali, Silat, or combatives to suit local audiences.

This expansion was decentralized—no singular body controlled Jeet Kune Do globally, and certification standards varied by lineage and teacher.

Diverging Identities in a Commercial World

As JKD reached broader audiences, the art encountered the same forces reshaping many traditional practices:

- Branding: Schools began marketing Jeet Kune Do as a unique product, often emphasizing Bruce Lee’s image over substance

- Franchise models: Some instructors created affiliate systems, which standardized teaching but raised concerns about dilution

- Hybridization: JKD became a component in broader MMA or self-defense programs, often stripped of its philosophical grounding

This period saw the rise of both purist and eclectic interpretations:

| Type | Description | Notable Traits |

|---|---|---|

| JKD Preservationist | Focuses on Bruce Lee’s original notes, structure, and philosophy | Faithful to LA Chinatown material |

| JKD Concepts Instructor | Sees JKD as an evolving art, open to new influences | Includes ground fighting, weapons, and sport training |

| Commercial JKD | Uses JKD branding with limited depth | Often associated with generic self-defense |

The tension between tradition and evolution remained unresolved, but it highlighted the adaptability—and fragility—of an art built on rejection of rigidity.

Digital Age, Revivalism, and Contemporary Adaptations

Online Transmission and the Democratization of Knowledge

The rise of the internet and social media in the early 21st century radically changed how martial arts knowledge was accessed, shared, and questioned. Jeet Kune Do saw a digital resurgence:

- Archival footage and rare Bruce Lee interviews were uploaded and dissected on forums and video platforms

- Instructional content became widely available through YouTube, Patreon, and online academies

- Disciples of Lee began teaching virtually, reaching practitioners across continents

While this increased visibility, it also introduced challenges:

- Fragmented teachings without live correction

- Misuse of terminology by unqualified instructors

- Echo chambers of dogma or misinformation

Nonetheless, the internet enabled serious practitioners to connect across borders, fostering discourse on JKD’s core principles and reclaiming its philosophical depth.

Return to Roots and Revivalist Movements

Amid commercial dilution, several practitioners initiated movements to return to the roots of Jeet Kune Do. These efforts emphasized:

- Studying Lee’s handwritten notes and training journals

- Reconstructing curricula from early disciples’ memories and archives

- Integrating Taoist, Zen, and philosophical elements once central to JKD’s ethos

Notable revivalist directions include:

- The Jeet Kune Do Nucleus, formed to preserve and share authentic material from Lee’s estate

- Independent study groups focused on the Seattle and Oakland phase of Lee’s development

- “No-nonsense” JKD branches focusing on practical drills, interceptive timing, and minimalism

This revivalist trend mirrors patterns in other martial arts, where periods of commercial excess often provoke a scholarly and practice-based return to origin.

Institutional Absence and Legacy Through Influence

Unlike many martial arts, Jeet Kune Do never formed a global federation or governing body. Its anti-institutional origins remain embedded in its DNA. As a result:

- There is no international belt system or rank hierarchy

- Quality control depends entirely on individual lineages and instructors

- JKD thrives more as a movement than a standardized art

Yet, Jeet Kune Do’s legacy is deeply embedded in modern martial arts:

- Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) adopted JKD’s emphasis on cross-training and realism

- Military and law enforcement systems cite JKD’s fluidity and efficiency

- Personal development coaches and athletes borrow Lee’s mindset for peak performance

Jeet Kune Do exists today not just in dojos, but in philosophy lectures, performance psychology, and cultural critique. Its global journey reflects the complexity of an artform born in rebellion, matured in ambiguity, and perpetuated by passionate seekers—not institutions.