Origins in Sahelian Society

Cultural Roots among the Hausa and Songhai

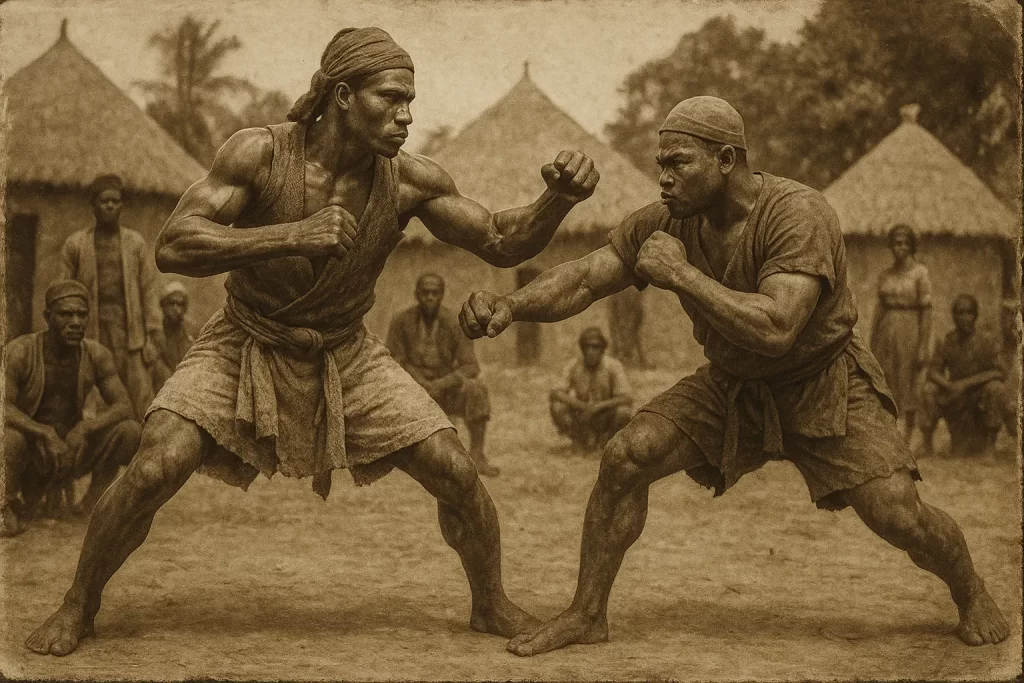

Danbe finds its origins in the cultural heartlands of the Sahel, primarily among the Hausa and Songhai peoples of present-day Nigeria, Niger, and Mali. Far from being a peripheral practice, early forms of Danbe were deeply woven into the fabric of social life, particularly among young men transitioning into adulthood. The practice was often tied to harvest festivals, communal gatherings, and warrior rites, reflecting its dual role as entertainment and training for future conflict.

- Among the Hausa, Danbe was closely linked to masquerade festivals and dry season celebrations, where villages hosted public matches in makeshift arenas.

- The Songhai, especially during the height of their empire, integrated hand-to-hand combat training as part of military instruction, where wrestling and striking traditions coexisted.

It is crucial to view Danbe not merely as a sport, but as a cultural institution—a proving ground for masculinity, discipline, and social hierarchy. The victor of a bout gained not just prestige but often material rewards, including livestock or marital prospects.

Danbe was not trained in secret but lived and breathed in the center of the community—on the sand, under the gaze of the elders.

The Role of Caste and Guild Traditions

Danbe’s early dissemination was tied to specific caste structures, particularly among the Hausa where certain occupations—including butchers, blacksmiths, and musicians—formed quasi-hereditary guilds. Notably, butchers (ma’aboki) were often linked to Danbe due to their physical strength and symbolic proximity to blood and raw power.

- These fighting castes often passed down techniques orally and through apprenticeship-style training, forming proto-lineages of fighters.

- Ritual elements, such as wrapping the striking hand in cloth and twine, had both symbolic and practical origins, thought to channel spiritual protection and emphasize dominance.

These early guilds served as more than training halls—they were guardians of a martial ethos rooted in work, tradition, and honor. The integration of music, particularly the talking drum and flute, into fights further cemented Danbe’s communal role.

Interplay with Indigenous Religion and Spirituality

Before the widespread spread of Islam in the Sahel, Danbe was practiced within the framework of indigenous animist beliefs. Combat was never just physical—it was spiritual.

- Fighters often sought blessings from traditional priests or diviners who provided charms (gris-gris) or invoked spirits for protection.

- Certain days were considered inauspicious for combat, based on lunar or ancestral calendars.

- Victors attributed their success not just to skill, but to the favor of the spirit world.

While later Islamic influence would reinterpret these practices, the foundational link between martial success and spiritual alignment remains a hallmark of Danbe’s early ethos.

Martial Evolution during Precolonial and Imperial Eras

Danbe in the Age of Empires

During the era of powerful West African empires—especially the Songhai Empire (15th–16th century)—Danbe underwent an important evolution. While the Songhai elite maintained cavalry-based warfare, foot soldiers and guards often engaged in rigorous unarmed combat drills, including forms reminiscent of Danbe.

- Historical chronicles from Timbuktu make occasional reference to public combats held in garrisons and frontier towns.

- Soldiers returning from campaigns brought back regional variations, helping to diffuse and diversify the practice across a wide territory.

As empires expanded, so did martial exchange. Danbe was not isolated—it absorbed and reshaped techniques through contact with Fulani herders, Tuareg caravans, and even distant trade cities connected via trans-Saharan routes.

Danbe became a language of dominance not only among villagers but among warriors patrolling the desert’s edge.

Influence of Migration and Urbanization

The precolonial period saw significant internal migration, prompted by both commerce and conflict. As Hausa city-states and other centers like Kano, Katsina, and Zaria flourished, Danbe entered an urban context.

- In urban centers, Danbe shifted from a seasonal, rural rite to a regularized urban spectacle.

- Permanent fighting rings and patronage systems emerged, with wealthy traders and chiefs sponsoring fighters, akin to proto-managers.

This transition mirrored broader changes in African martial traditions, where mobility of fighters led to hybridization of styles. Danbe slowly gained a reputation beyond ethnic lines, becoming an intercultural contest within bustling trade hubs.

Early Notions of Technique and Lineage

Even in this early period, certain techniques and fighter traits began to be codified, albeit orally. Fighters were known for:

- The dominant hand (typically the right) used for striking, often wrapped and weighted

- The guarding hand, left unwrapped, reserved for defense or balance

- Emphasis on aggressive footwork, often mimicking animal movements

Some oral traditions even recount named champions, such as a legendary figure known only as Gwarzon Gari—the city’s pride—said to have fought undefeated for seven dry seasons in Zaria. While historical verification is elusive, such stories point to early seeds of lineage and myth in Danbe culture.

The Structuring of Tradition in Colonial Context

Colonial Disruption and the Survival of Danbe

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a profound shift for Danbe, as European colonial powers—particularly the British and French—imposed administrative control over West Africa. Many indigenous practices were suppressed or dismissed as primitive. Danbe, with its public displays of aggression and deep roots in Hausa culture, was often viewed with suspicion.

- In French West Africa, colonial decrees banned public matches in urban areas under the guise of civil order.

- British authorities in Northern Nigeria tolerated Danbe in rural zones but discouraged its association with youth mobilization.

Despite this repression, Danbe persisted in secret and in periphery. Rural communities and local guilds kept it alive, often under the radar of colonial rule. Fighters trained in secluded clearings, and elders continued oral transmission through metaphor and song.

Danbe became both a symbol of cultural resistance and a coded language of defiance, its forms hidden in plain sight among livestock fairs and festival rituals.

Emergence of Local Patronage Networks

Paradoxically, the colonial economy—through cash crop production and railway labor—created new nodes of mobility. Urban migration increased, and with it, a resurgence of Danbe in marketplaces and labor camps.

- Merchant elites and regional chieftains began sponsoring fighters, reviving the custom of patron-backed combat.

- Towns like Zaria, Kano, and Maradi developed informal circuits where notable fighters could build reputations.

This patronage system seeded the early formations of fighting families or guild dynasties. Certain surnames—often tied to trades like butchery—began to dominate the scene. Knowledge was now curated within household units, passed from father to son, uncle to nephew.

Fusion of Regional Techniques and Identity

The colonial period also witnessed growing cultural fusion. Migrant fighters encountered different local styles—wrestling (kokawa), stick-fighting (dongo), and even influences from Sahelian cavalry drills.

Danbe absorbed these inputs:

- Fighters began integrating balance-breaking footwork from Kokawa

- The guarding arm took on more defensive parries, borrowed from Fulani staff techniques

- Naming conventions emerged, such as “the striker’s hand” (hannun daka) and “the anchor leg” (kafa tushe)

This era laid the groundwork for the technical lexicon of Danbe. Though still transmitted orally, an internal coherence in vocabulary and principles began to crystallize—setting the stage for structured pedagogy.

Rise of Lineages and Semi-Formal Schools

Foundational Figures and the Birth of Schools

In the mid-20th century, Danbe began to transform from an ad hoc village tradition into a school-based art form. Central to this evolution were master fighters who not only excelled in competition but took on structured roles as mentors and founders.

One of the most widely cited figures is Malum Audu of Kano, a former blacksmith and market champion who systematized training routines for his apprentices.

- He emphasized sand-pit drills, one-armed sparring, and footwork circuits

- His compound became known as the Gidan Dambe (House of Fighting), attracting students from across the Sahel

Other masters followed suit, founding their own houses and instituting rules of discipline, progression, and clan loyalty. While still informal by global martial standards, these houses represented a clear evolution toward semi-formal schools.

Technical Codification and Teaching Progression

By the 1960s, a growing number of houses began to establish training hierarchies. Although there was no belt system, distinctions emerged between:

- Yaran Dambe (young apprentices)

- Zakaran Dambe (combatants)

- Jagaban (champions or clan leads)

Training cycles mirrored seasonal work: the dry season (post-harvest) was intensive, while the wet season saw light conditioning.

Common teaching tools included:

- Repetition drills: emphasizing single-hand strikes and stance control

- Music-timed footwork: matching drum rhythms to evasive steps

- Challenge sparring: rotating opponents across rounds to test reflex under fatigue

These methods formalized Danbe’s pedagogy while retaining its oral and performative roots.

Divergence of Philosophical Interpretations

As houses expanded, differences in training emphasis and worldview began to emerge. Some lineages, especially in rural Niger, maintained a strong ritualistic component, integrating invocations and spirit offerings before matches. Others, especially in northern Nigeria, shifted toward a more pragmatic and secular approach, favoring athleticism over mysticism.

This divergence introduced a soft polarization:

- Mystic-ritual houses: emphasized spiritual lineage, charms, and taboos

- Modernist houses: focused on competition readiness, physical conditioning, and cross-style adaptability

Such divisions were not hostile, but they created distinct identities. A fighter’s reputation became tied not only to victory, but also to the philosophy of their house—whether mystical, physical, or hybrid.

Modernization, Standardization, and Institutional Shifts

Postcolonial Revival and National Identity

The mid-20th century marked a critical turning point for Danbe, as newly independent African nations sought to reclaim and elevate indigenous traditions that had been marginalized under colonial rule. In Nigeria and Niger, Danbe was revalorized not only as a martial heritage but as a symbol of cultural identity.

- Government cultural ministries in the 1970s included Danbe demonstrations in national festivals and Independence Day events.

- Ethnographic research and academic interest from Nigerian universities contributed to documenting Danbe history and lineage.

This postcolonial revival reframed Danbe as a heritage art, offering legitimacy to its practitioners and motivating younger generations to view it as a proud, African-rooted discipline rather than a relic of the past.

Danbe emerged from the margins to become a cultural emblem of postcolonial resilience and self-definition.

Emergence of Urban Arenas and Semi-Professional Circuits

Urbanization throughout the 20th century brought Danbe out of village clearings and into the amphitheaters of modern African cities. Kano, Zaria, and Lagos became major centers of activity, where Danbe fights were staged not only for community celebration but also as ticketed public events.

This shift led to the rise of:

- Fighter stables managed by former champions and entrepreneurs

- Organized fight nights, often with drummers, announcers, and matchmakers

- A semi-professional status for top fighters, some of whom earned substantial prizes or gained celebrity status

However, this commercialization raised debates within the Danbe community. Critics argued that entertainment-driven formats diluted the spiritual and communal essence of the art. Others saw it as a necessary evolution, helping fighters earn livelihoods and expanding the art’s visibility.

Birth of Danbe Federations and Organizational Efforts

By the late 1990s and into the 2000s, various attempts were made to formally institutionalize Danbe. These efforts were led by both local advocates and diaspora communities seeking to unify scattered practices under common frameworks.

Notable milestones include:

- The Nigerian Traditional Sports Federation (NTSF), which incorporated Danbe under its umbrella in select regional competitions

- Attempts in Niger and Benin to create cross-border networks of houses and promote intercultural tournaments

- Informal councils of elders and retired fighters collaborating on guidelines for safety, training ethics, and lineage preservation

Although no singular global federation has emerged, these local efforts represent early steps toward the formal organization and protection of Danbe as a living martial tradition.

Digital Expansion, Diaspora, and Cultural Crossroads

Migration, Diaspora, and International Curiosity

Migration patterns in the late 20th century brought Danbe practitioners into new contexts, particularly across Europe and North America. While initially fragmented, these diasporic communities began to reconstruct Danbe practices abroad, often adapting to new environments.

- Some fighters taught Danbe in West African cultural centers in Paris, Brussels, and New York.

- Pan-African festivals and martial arts expos showcased Danbe as part of African cultural programming.

Interest from non-African martial artists and anthropologists also grew, particularly those curious about Africa’s underrepresented combat systems. Danbe was increasingly featured in academic documentaries, comparative fighting studies, and ethnomartial publications.

Online Media, Global Audiences, and Cultural Tensions

The 2010s marked a new chapter in Danbe’s visibility: online video platforms, such as YouTube and Facebook, began circulating recordings of dramatic matches—often shot in the sand arenas of Kano or Maradi. These clips garnered millions of views and introduced Danbe to global audiences unfamiliar with African martial traditions.

This exposure, however, introduced tensions:

- Fighters became content celebrities, sometimes incentivized to stage more theatrical or brutal matches for clicks.

- Non-African viewers interpreted Danbe through exoticizing or sensationalist lenses, ignoring its deep cultural frameworks.

Meanwhile, younger practitioners began offering online tutorials, interviews, and history lessons, seeking to balance fame with fidelity. Social media became both a stage and a battleground, where the soul of Danbe was being negotiated.

Return to Roots and Revivalist Movements

In response to commercialization and misrepresentation, a growing number of practitioners initiated revivalist movements. These groups emphasized returning to Danbe’s ritual, ethical, and communal dimensions, often drawing on pre-Islamic and precolonial symbolism.

Revivalist goals included:

- Archiving oral histories and recording the memories of aging masters

- Reintegrating musical, spiritual, and ritual components into training

- Reestablishing Danbe as a rite of passage, not just a performance art

Some houses began holding closed, non-public sessions, prioritizing cultural depth over spectacle. These efforts marked a reinvestment in Danbe’s ancestral identity, seeking to transmit not just a set of movements—but a worldview rooted in West African cosmology, rhythm, and resilience.