The Roots in Enslavement and Resistance

Angola and the Bantu Cosmology

The genesis of capoeira lies in the cultural matrix of Central and West Africa, particularly among the Bantu-speaking peoples from Angola and Congo. These communities brought with them not only language and religion but also embodied traditions of movement, rhythm, and ritual combat. The spiritual foundations of capoeira can be traced to Bantu cosmology, where the circle (kalunga) symbolized the boundary between the world of the living and the ancestral realm. In many rituals, dance and combat were not separate but intertwined – expressive forms like ngolo, a ritual game believed to simulate zebra combat, were both performance and initiation.

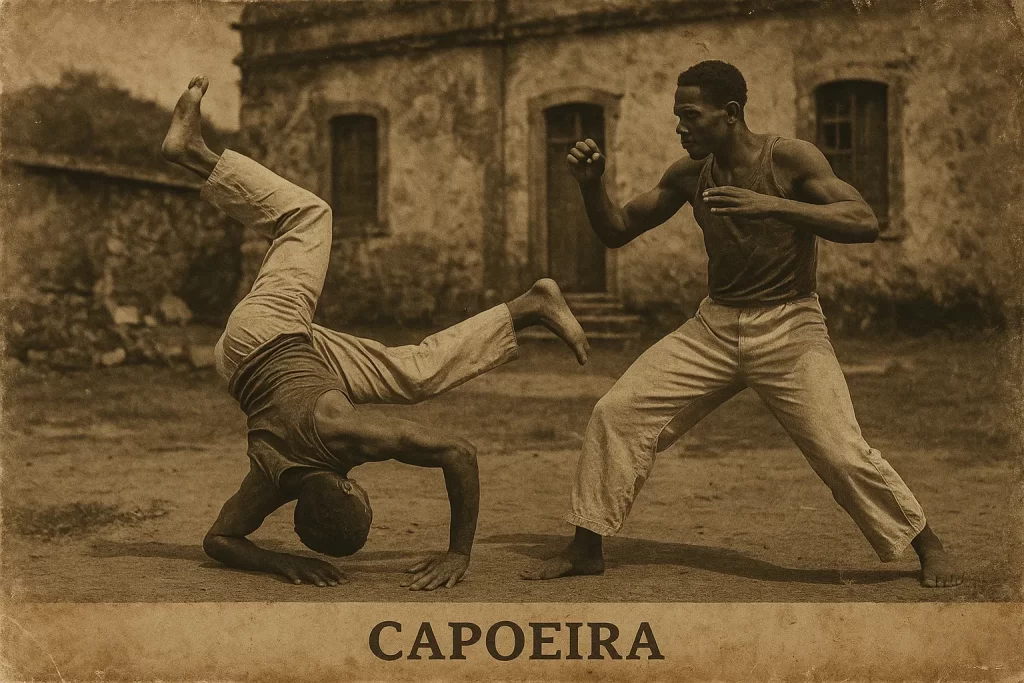

Ngolo, characterized by agile kicks, inverted movements, and circular patterns, is often considered a proto-capoeira system. It was practiced during rites of passage and served both a spiritual and physical purpose. These martial-dance expressions did not aim to kill but to demonstrate skill, control, and inner power – elements later mirrored in capoeira’s aesthetic.

The Middle Passage and Cultural Transplantation

The transatlantic slave trade violently uprooted millions of Africans, particularly from Angola and Mozambique, and transplanted them to Brazil under Portuguese colonial rule. This massive displacement brought profound suffering, but also set the stage for cultural resistance. Enslaved Africans in Brazil recreated fragments of their spiritual and cultural worlds, merging diverse ethnic practices under conditions of extreme repression.

In this process, ngolo and other ancestral games adapted to the new social environment. Though stripped of overtly sacred elements to avoid punishment, the core ideas of circularity, trickery, and symbolic combat endured. These early forms of capoeira, likely practiced in the senzalas (slave quarters) and quilombos (runaway settlements), retained spiritual undertones even while evolving into instruments of survival and identity.

Note: The term capoeira likely emerged in the 18th century and referred both to the practice and to the practitioners, often associated with marginalized or criminalized populations in colonial Brazil.

Syncretism with Indigenous and Iberian Influences

While rooted in African traditions, capoeira did not develop in isolation. Indigenous Brazilian practices and Iberian cultural expressions influenced its evolution. Native games such as huka-huka (a form of wrestling among the Xingu peoples) and Iberian folk dances contributed movement patterns and performance frameworks. Furthermore, Catholic festivities like festa de São João provided public spaces where enslaved people could gather, masked by religious celebration.

Portuguese fencing traditions, such as the use of blades and dodging footwork, also left an imprint. Capoeira gradually became a hybrid system — part ritual, part survival strategy — that merged movement, music, and evasion into a uniquely Brazilian form of expression. The blend was not accidental but a result of adaptive resistance: every kick disguised as a dance, every step loaded with historical weight.

The Colonial Pressure and Evolution in Resistance Communities

The Role of Quilombos in Shaping Practice

One of the most critical environments for capoeira’s early development were the quilombos — autonomous settlements formed by escaped slaves and marginalized people. Among them, Quilombo dos Palmares stood out as a symbol of black resistance. Lasting for nearly a century (1605–1694), Palmares became a melting pot of African traditions, allowing martial knowledge to be preserved and developed under the leadership of figures such as Zumbi dos Palmares.

In such communities, capoeira was more than a game; it was a tool for collective defense. Tactics of ambush, evasion, and mockery evolved in response to colonial patrols and military incursions. Training took place in clearings (also called capoeiras), where movement could be rehearsed in a communal, circular format – possibly the forerunner of the roda.

- Capoeira in quilombos was:

- A method of stealth and armed resistance

- A mnemonic tool for preserving collective memory

- A symbol of liberation and ancestral connection

Hidden Transmission and Oral Lineages

Due to the criminalization and suppression of African practices in colonial Brazil, capoeira was forced underground. Transmission of knowledge occurred through oral tradition, songs, and symbolic play. There were no written manuals; instead, mastery was recognized through observation, repetition, and participation in the roda.

Songs functioned not just as rhythm-makers but as coded lessons. They referenced battles, masters, betrayals, and escapes — turning history into melody. Initiation often involved apprenticeship to a respected elder, and knowledge of movement was inseparable from an understanding of history, rhythm, and cunning.

Some early names survive in oral tradition — legendary Besouro Mangangá from Bahia, known for his supernatural agility and daring, is one such figure. Whether entirely historical or mythologized, such personalities represent archetypes of cunning resistance and spiritual mastery.

Criminalization and the Urban Underground

By the early 19th century, especially in port cities like Rio de Janeiro, capoeira was associated with maltas — urban gangs formed by marginalized black and mixed-race men. These groups often used capoeira as a system of defense, intimidation, and social bonding. The colonial and early imperial governments responded with repression, officially banning capoeira and criminalizing its practice under vagrancy laws.

Police records from the 1800s detail encounters with armed capoeiristas who combined kicks, dodges, razors, and even sticks (pau) in their confrontations. Capoeira thus entered a new phase: from a spiritual-cultural expression in rural and resistance communities to a street-savvy, politicized, and persecuted urban practice.

Capoeira’s association with subversion would last well into the 20th century, shaping its secretive evolution and deepening its role as a symbol of defiance.

From Margins to Method: The Birth of Structured Practice

Mestre Bimba and the Foundation of Luta Regional Baiana

In the early 20th century, capoeira remained suppressed, often associated with criminality and poverty. This changed dramatically with the efforts of Manoel dos Reis Machado, better known as Mestre Bimba, who sought to reform capoeira and secure its legitimacy.

Born in Salvador, Bahia, Bimba developed a new pedagogical system called Luta Regional Baiana, which integrated capoeira techniques with elements of effective self-defense, physical conditioning, and structured training. His aim was to remove the stigma of capoeira as a street brawl and elevate it as a disciplined martial art.

Key features of Bimba’s reform:

- Codified sequences (sequências de ensino)

- Introduction of uniforms and ranks

- Requirement of academic performance and moral conduct

- Use of Portuguese instead of African dialects in class

In 1932, Bimba opened the first official capoeira academy, marking a turning point. His students included professionals and members of the middle class, which helped legitimize the art among Brazilian elites.

Mestre Pastinha and the Preservation of Angola

While Bimba focused on reform, another figure emerged to preserve the traditional, ritualistic aspects of capoeira. Vicente Ferreira Pastinha, known as Mestre Pastinha, championed the style known as Capoeira Angola, emphasizing its Afro-Brazilian roots, philosophical depth, and ritual integrity.

Pastinha’s academy, founded in Salvador in 1941, was modeled after a philosophical society as much as a martial school. He insisted on:

- The ritual of the roda as a sacred space

- Preservation of African rhythms and instruments

- Slow, strategic, and expressive play

- Artistic and ethical education over competitiveness

Pastinha wore a yellow and black uniform, inspired by his favorite soccer club, and framed his teaching as a cultural mission rather than a sport or system of defense. His students became key preservers of the Angola lineage, including Mestre João Grande and Mestre João Pequeno.

Note: The philosophies of Bimba and Pastinha would later evolve into two dominant lineages: Regional and Angola, often seen as complementary rather than opposing traditions.

Legal Recognition and Institutional Shifts

The growing popularity and institutional structure introduced by Bimba and Pastinha eventually compelled the Brazilian state to re-evaluate its stance on capoeira. In 1937, Mestre Bimba was invited to demonstrate capoeira before President Getúlio Vargas, who declared it Brazil’s national sport.

Following this event:

- Capoeira academies began receiving official permits

- Police persecution of capoeiristas declined

- Capoeira entered the curricula of cultural and military institutions

The government’s acceptance of capoeira reflected broader nationalist trends — seeking to reframe Afro-Brazilian traditions as part of a unified Brazilian identity. Yet this came with consequences: the art was increasingly seen through the lens of performance, nationalism, and discipline rather than resistance and ritual.

Evolution of Lineages and the Rise of Pedagogical Models

Expansion of the Regional Model

Mestre Bimba’s Regional model expanded rapidly during the mid-20th century, especially in urban centers. The appeal of structured training, uniforms, ranking systems (cords or cordões), and physical discipline made it more accessible to institutions like the military, universities, and even police academies.

Core features of the Regional model included:

- Emphasis on precision and efficiency

- Faster rhythm (São Bento Grande de Bimba)

- Objective evaluation through sequences and grading

- Adaptability to formal instruction

Graduates from Bimba’s lineage began opening their own schools across Brazil. While some maintained close fidelity to Bimba’s curriculum, others introduced hybrid innovations, incorporating elements from boxing, judo, or gymnastics.

The disciplinary framing of capoeira also led to internal debates. Was capoeira losing its soul in the process of becoming respectable?

Divergence and Resistance in the Angola Tradition

In contrast to the codification and expansion of Regional capoeira, Angola lineages often resisted formalization. While Mestre Pastinha did introduce uniforms and a fixed location for training, many Angola practitioners preserved a looser structure, oral transmission, and emphasis on lived philosophy.

Important characteristics of Angola schools:

- Preference for traditional rhythms (Ladainha, Chula, Corrido)

- Teaching through the roda rather than rote sequences

- Use of metaphor, song, and improvisation as teaching tools

- Emphasis on malícia (cunning, trickery) over brute force

Despite institutional neglect and occasional marginalization, the Angola tradition flourished in neighborhoods and cultural centers. Masters like Mestre Moraes and Mestre Nô helped maintain a rich oral tradition and emphasized the connection between capoeira, Afro-Brazilian identity, and resistance to cultural erasure.

Angola lineages were often deeply embedded in community activism, carnival culture, and Afro-Brazilian religion (particularly Candomblé), blurring the line between martial art and socio-spiritual practice.

Hybrid Movements and New Schools of Thought

By the 1960s and 70s, a growing number of capoeiristas sought to move beyond the binary of Angola vs. Regional. These innovators began to integrate elements from both styles, often combining:

- Angola’s emphasis on ritual and rhythm

- Regional’s structure and athleticism

- Contemporary needs for pedagogy, visibility, and versatility

This led to the emergence of what is now known as Capoeira Contemporânea (Contemporary Capoeira). It often adopted:

- More fluid hierarchy and ranking systems

- Innovative music and movement blends

- Emphasis on artistic expression, education, and social projects

Key figures in this phase include Mestre Acordeon, who helped disseminate capoeira through academic and cultural avenues, and Mestre Suassuna, founder of the influential Grupo Cordão de Ouro.

This period marked the beginning of capoeira’s reinvention for a broader audience, while still tethered to its historical and cultural roots — a transition that would set the stage for global expansion.

Capoeira Across Borders: Diaspora, Media, and Institutional Growth

Post-Dictatorship Cultural Renaissance

In the aftermath of Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964–1985), capoeira experienced a new phase of cultural resurgence. The lifting of state censorship and the revitalization of Afro-Brazilian identity gave capoeiristas renewed space for expression, research, and organization.

Capoeira became a symbol of resilience, creativity, and national heritage. During this time:

- Cultural funding supported preservation projects

- Academic research on Afro-Brazilian traditions expanded

- Capoeira was taught in public schools and community centers

- Capoeira appeared in theater, music, and televised events

The movement also aligned itself with broader struggles for racial justice, especially within Brazil’s urban peripheries. Masters such as Mestre Cobra Mansa and Mestre Neco connected capoeira with black empowerment and historical memory, reaffirming its African roots within a modern political framework.

Migration and the Rise of Global Mestres

Starting in the 1980s and 1990s, a growing number of Brazilian capoeiristas emigrated to Europe, North America, Asia, and Africa. These practitioners, often trained in the Regional or Contemporânea styles, began to establish academies and cultural groups abroad.

This diaspora was shaped by:

- Artistic exchange programs and international festivals

- Demand for Afro-Brazilian cultural products

- Personal migration motivated by opportunity and exploration

- Global martial arts communities seeking alternative systems

Notable global ambassadors include Mestre Acordeon, who settled in the U.S. and combined capoeira with storytelling and cultural diplomacy, and Mestre Marcelo Caveirinha, who introduced capoeira into Hollywood fight choreography.

Today, capoeira is practiced in over 160 countries, often integrated into:

- University curricula

- Youth outreach programs

- Dance and fitness industries

- Multicultural festivals and expos

However, global diffusion has led to a fragmentation of pedagogical standards and varying interpretations of lineage and legitimacy.

Online Platforms and Digital Reinvention

The 21st century brought capoeira into the digital age. Websites, forums, and eventually social media platforms became key tools for preserving history, sharing knowledge, and building transnational networks.

Major developments included:

- Online rodas via video conferencing

- Instructional YouTube channels and Patreon-supported schools

- Capoeira-themed podcasts, blogs, and digital archives

- Global festivals streamed in real time

These tools democratized access to information, but also challenged traditional forms of oral transmission. Debates emerged around:

- The dilution of ritual

- Virtual teaching vs. physical presence

- Cultural appropriation vs. global outreach

Some traditionalists viewed digital capoeira as a break from ancestral modes of learning. Others embraced it as a necessary evolution, especially during events like the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced schools to adapt or close.

Tensions and Continuities: Tradition, Identity, and Revival

Institutionalization and Competitive Frameworks

The global rise of capoeira created pressure for standardization. Organizations like ABCA (Associação Brasileira de Capoeira Angola) and CBCE (Confederação Brasileira de Capoeira Esportiva) emerged to codify ranking systems, competition formats, and instructional guidelines.

Some schools adopted a sports-like approach, incorporating:

- Tournaments and judging criteria

- Official belts or cordas with colored progression

- Alignment with Olympic-style governance

This shift was polarizing. While some saw it as necessary for capoeira’s international credibility, others warned that sportification threatened the art’s philosophical and ritual dimensions.

Major concerns among traditionalists included:

- Loss of axé (spiritual energy)

- Oversimplification of song and language

- Prioritization of acrobatics over malícia and ritual play

Note: Unlike other martial arts, capoeira’s essence lies not only in efficiency or performance, but in narrative, resistance, and cultural continuity — elements not easily captured by sporting models.

Revivalist Movements and Return to African Heritage

In response to perceived dilution, several movements emerged aiming to reclaim capoeira’s African essence. These initiatives emphasized:

- Connection to Bantu cosmologies

- Use of ritual language and traditional music

- Study of slavery-era practices and quilombo history

- Training in cultural context rather than performance

Projects like Kilombo Tenondé and educational collectives in Angola and Mozambique explored shared ancestry and spiritual parallels between African games and capoeira. Some mestres traveled to Africa not as missionaries, but as cultural pilgrims seeking deeper understanding.

Revivalist movements also critiqued the whitening of capoeira in global media, advocating for the visibility of black Brazilian and African voices in leadership roles.

Key figures in this effort include:

- Mestre Nô, one of the last living students of early 20th-century Angola masters

- Mestre Paulão Kikongo, who foregrounds Kongo-Angolan philosophy in capoeira

Hybridization, Identity, and the Path Ahead

Contemporary capoeira exists in a state of creative tension. Globalization has multiplied its forms: from urban youth activism to stage spectacle, from cultural diplomacy to cross-training in MMA. Its fluid identity allows for rich fusions, but also raises questions about authenticity and direction.

Forms of hybridization today include:

- Capoeira fused with breakdancing and parkour

- Workshops in trauma healing and body awareness

- Gender-focused rodas and queer-led schools

- Blends with West African drumming, samba, or yoga

Yet even as capoeira expands, many schools continue to uphold foundational elements:

- The circle of the roda

- The interplay of music, movement, and message

- The role of elders and oral transmission

Capoeira’s future lies not in choosing between tradition and innovation, but in navigating their dialogue — honoring its past while reshaping itself for a changing world.

If you’d like, I can compile all three parts into a single formatted document or create supporting material such as quotes, timelines, or glossary terms for your Capoeira section.